Estonians outside Estonia

(Chapter 1, pp. 1-18)

Estonians have lived for generations in the area between the Baltic Sea and Lake Peipus. Before the proclamation of the Republic of Estonia in 1918, about 300,00 Estonians lived outside their ancestral homeland. But after Estonia lost its independence in the 13th century, it was not until the reforms of the early 19th-century and the rapid rise in urbanization that opportunities arose for emigration. According to census data, the natural increase in population of the province in the Livonia "gouvernment" (Southern Estonia) between 1881 and 1897 was 139,072. During the same period, 146,085 left the area. The same, source places the natural increase in population of the provinces in the "governement of Estonia" (Northern Estonia) at 45,498, the number emigrating at 26,386. The largest Estonian settlements were in Russia. During the 19th century many Estonians also went to the United States of America.

The second half of the 19th century saw massive emigration as people left Estonia in search of better living conditions and greater freedom. Estonian settlements arose in the Crimea, Caucasia and the area east of Lake Peipus in Russia. In fact, according to the Russian census of 1917, there were in the Oudova prairie east of Lake Peipus about 40,000 Estonians, who formed 25 percent of the total population there.

The next wave of emigration - from the Estonian settlements in Russia - saw many leave for Canada and the United States. Because it was not customary for lands to be divided among sons and heirs, most of those who followed this route were the landless younger sons of Estonian settlers. At that time free land or homesteads could be obtained, in the United States and Canada. A sizeable portion of the first Estonian settlers in Alberta came from the Estonian settlements in Russia, especially from Nurmekunda in the Tver "gouvernement."

Under the 1920 peace treaty between Estonia and Russia, it was possible for Estonians from Russia to opt to return to their homeland. About 40,000 of the more than 200,000 Estonians in Russia took up the offer. Most of them were educated people and professionals. Of the farmers and entrepreneurs, only those from nearby locations returned to Estonia. The general chaos, epidemics and difficult travel conditions of postrevolutionary Russia hampered the movement to return to Estonia.

For the Estonians who stayed in Russia, statistics are available for 1926, according to which there were 154,600 Estonians (35,500 urban-and 119,100 rural), of whom 139,500 spoke Estonian. Although there is no general survey available of the fate of Estonian settlements in Russia under Communist rule, the socialization of village life, the collectivization of agriculture and the liquidation of the kulak (rich peasant) class certainly destroyed the formerly prosperous Estonian settlements.

Emigration from independent Estonia took place in the years 1920-1940 as people searched for better economic conditions. The peak of emigration was 1925 and 1926, with 2,676 and 2,426 emigrants respectively, and total emigration in this period was about 17,000. The major destinations were the United States, Brazil and Canada.

In the United States, Estonian farmers founded four large Estonian settlements. The Koidu settlement in South Dakota dates from 1892. The largest Estonian settlement in Wisconsin was the village of Irma, 15 miles from the town of Mernell. In North Dakota there was an Estonian settlement near Dickenson, founded in 1902. The fourth was the Laane settlement in Montana, near Chester, settled in 1905-09 mostly by Estonians from Russia. The total number of Estonians who settled in the United States has never been determined. One reasonable estimate is 69,000, which the American authorities used in 1920 in determining the quota of Estonian immigrants to be allowed entry into the United States. In the 1930s it was estimated that about 50,000 U.S". citizens could speak Estonian.

The number of post-World War I Estonian immigrants to the United States totalled 13,516. In Autralia, there were in 1939 897 persons born in Estonia. The corresponding figure for 1947 was 1,102

In South America the largest group of Estonians were the 3,000 who went to Brazil between 1925 and 1926. A few thousand lived in Helsinki and Riga. At the beginning of World War II, many Estonians left their homeland in the company of Baltic Germans who resettled in Germany.

All of the above-described emigration was voluntary. The massive flight from Estonia in September 1944 took place suddenly under drastically different conditions. The Soviet forces were on the offensive to occupy the Baltic States for the second time. A regime of terror founded on violence was approaching. A part of Estonia was already under its grip.

Fleeing as a refugee meant taking great risks. The sea was perilous. Small craft overloaded with passengers were unsuited for deep-sea voyages in the gathering autumn storms. The refugee ships were attacked mercilessly. Not everyone could choose that hazardous route which led to the shores of Sweden, nor even the alternative: heading for war-torn Germany. The Russians had already started to attack the refugee craft with submarines and air raids. It is estimated that between 1,000 and 1,200 Estonians died at sea on the way to Germany. About 200 Estonians died in the bombing of Dresden. The 800 refugees who found themselves in Denmark at the end of the war had come via Germany.

In 1947 and 1948 about 7,000 Estonians were able to leave Germany for Great Britain under labor agreements. From 1947 on 6,228 Estonians emigrated from Germany to Australia. About 27,000 Estonians left Germany after several years in the displaced persons' camps and settled, overseas. The number of Estonians who fled to Sweden in 1944 and 1945 was estimated at 22,000.

According to government statistics 282 Estonians arrived in Canada in 1947. The next year their numbers increased dramatically, reaching 1,903 and in 1949 2,945. The figure for 1950 declined to 1,949, climbJng in 1951 to 4,573 and falling again in 1952 to 1,350. In 1952 there were 16,000 Estonians in Canada. According to the 1961 census there were 18,500 Estonians in Canada. Their numbers in the early 1970s were estimated at approximately 20,000.

The Estonians in Canada before World War I

(Chapter 2, pp. 19-62)

During the last quarter of the 19th century emigration from Europe to North America increased markedly. In Estonia, as elsewhere, it was well known that a poor man could find unlimited economic opportunities and freedom in the New World. In the 1870s enormous tracts of land in Canada, especially in Alberta, were still vacant. Every settler who was at least 21 years old could by law obtain one quarter-section of land as a homestead for only $10. If after three years, he had at least 15 acres under cultivation, he could obtain ownership of òthe land, and for $2 to $2.50 an acre he could buy more.

The Estonian settlers, who began to come to Alberta toward the turn of the century established seven identifiable settlements. Livonia, near the present town of Sylvan Lake, was the spot where the first Estonian homesteaders, Hendrik Kingsep, a schoplteacher from Nuustaku in the province of Võrumaa, and his brother Kristjan, a seaman, settled in 1899. The land they chose for their new home was wild and untamed, the climate harsh and the weather unpredictable. Despite this, the bountiful growth of grass in the meadows and burnt woodlands gave fodder for cattle. Fish and game were plentiful, and there was no shortage of building materials. The enterprising brothers built a log cabin and furnished it themselves.

The horses which the-settlers had bought on the Prairies were unsuited for the uplands and died. As a result, they had to use slow oxen and mules as draft animals. Their first crops were vegetables and potatoes. They raised pigs and chickens and kept dairy cattle. The settlement grew rapidly and by early 1901 there were five Estonian families totalling 16 people in the Sylvan Lake area. That fall new settlers came from both the Estonian island of Saaremaa and the Nurmekunde settlement in Russia. By the end of 1903 the settlement had grown to 16 farmsteads with a total population of 61. The first school in Livonia was built in 1903 on two acres of land donated by Juhan Kask. Later the Norma School was built on lands belonging to the Tiina farm.

As the Sylvan Lake area became densely settled, Estonians began to seek new lands. They chose Medicine Valley near Eckville, 24 miles to the west. The settlement was founded by Hendrik Kingsep and August Posti, who left Livonia on October 26, 1902. The Medicine Valley area was enchanting to the first Estonian settlers from Võrumaa and southern Tartumaa. The valleys, bluffs and wooded hills, dotted with lakes and small rivers, reminded them of home. But it took time and effort to exploit the riches of the valley. Despite initial hardships the Medicine Valley still seemed like a promised land. Its renown spread quickly to the first settlers' homelands in southern Estonia. As a result the very next year 23 new settlers arrived. They were followed in later years by new groups from Tartu, Võrumaa and elsewhere in Estonia. Although 16 people left the settlement during this first period and 11 died, by the end of the era the Medicine Valley Estonian colony had a population of almost 160.

Because the settlers lacked cash, they had to find paying jobs off the farm, mostly in cities. A man could earn $2 for a 10-hour workday on the CPR lines, although 67 cents was deducted for meals. Through hard work, every settler had his own house and the necessary 15 acres under cultivation after three years, which entitled him to ownership of his homestead.

Each settler had enough woodland to furnish lumber for a house. The walls were built of logs covered with clay, and moss was stuffed into the cracks on the inside. The roof was built of rough lumber covered with sod or hay, later replaced with wood shingles.

Grain crops were slow to develop at first because the virgin lands required machines and draft animals which the settlers could not afford. Potatoes, cabbages, carrots, onions and turnips were initially the only sustenance and source of income. The first cereal crops were rye, barley and oats, wheat being added later on. To overcome the hardships of the first years, the settlers helped each other with plowing and other tasks. Cattle and chickens were the main sources of income.

Major changes took place between 1908 and 1910. By then, most settlers had acquired a measure of financial strength and no longer had to find jobs off the farm. Additional income could be earned in milling. Fritz Kinna learned how to build dams and work with concrete while working on railway bridges, and used hjs new skill to build a mill on the Medicine River. Another mill was built by Juhan Mäesepp. Mart Sestrap had a small windmill, and Karl Moro built a large gristmill and dam on the Medicine River. Later it was converted to steam where business grew, and later still it supplied electricity to the ent''3 town of Eckville". la step with the gradual cultivation of forest and bush and with improved implements, the settlers went from livestock production to mixed farming and later exclusively to grain crops.

Once the Medicine Valley settlers were reasonably established, their first concern was educating their children - far from any major centre. Their only alternative was to establish a local school. The government supplied the schoolhouse plans, the construction foreman and a teacher. Karl Langer sold the land for $1 per acre and Estonian settlers constructed the school and furniture. It was the first in the area and was formally inaugurated on the Estonian feast of St. John's Eve on dune 24, 1909, and officially named Estonian School. The one-room school provided instruction in Grades 1 to 8 in English only. As well, the school became the focal point of the community as a place for meetings, social gatherings and parties.

Organized social and cultural activity began with the founding of the Medicine Valley Estonian Association (MVEA) on April 24, 1910. Within a few years the association had become the focal point for community life. A choir and band, which had been established about 1906, performed regularly at social events and parties and were also in great demand outside of the Estonian settlement. Both the choir and band joined the MVEA. As well, an active theatre company gave performances at each gathering and, together with the choir and band, made guest appearances at the Linda Hall in Stettler. With the founding of the Estonian association and school, the Medicine Valley settlement became active in the entire Eckville area.

The idea of building a communiy hall had been discussed since the beginning of Estonian settlement in Medicine Valley, but due to disputes over whether it should be constructed by the association or by a corporation, the Estonian Hall was not built until 1918 under the auspices of the MVEA. Its opening ceremonies were a major event attended by great crowds. As well, one of the most important activities of the MVEA was the founding of a library. At the time of the first annual meeting in 1911 the library contained 73 purchased volumes and nine donated ones. By 1915 the collection had grown to 244.

The largest and most lasting enterprises were the founding of the local branch of the farmers' union in. 1911 and establishment of a Savings and Loan Spciety for the members of the MVEA in 1912. A farmers' cooperative was founded in Eckville the same year.

The Estonian settlement at Stettler was established in 1904 by Magnus Tipman and Mihkel Kutras when six families.moved there from Sylvan Lake. The number of Estonian settlers who chose homesteads in Stettler that year rose to almost 25. This settlement grew rapidly and by 1910 there were 45 farms with a population of 171. In 1905-1906 the railway reached Stettler, bringing even more settlers to the area. Although all the lands were soon settled, about 20 miles to the south in Big Valley land was still available.

A new Estonian village known as Kalev was founded there with a total of 15 families. At the first community meeting in 1905 the Stettler homesteaders named their locality Linda.

At the recommendation of Pastor Sillak, an itinerant pastor from Medicine Hat who served the Estonian settlements, 10 acres of government land in Linda were obtained for a church. The southwest corner was dedicated as a cemetery. St. John's Lutheran congregation was established. The following year Pastor Sillak told the congregation that if a church was not built, the land would revert to the government. A meeting was called and it was decided that the church would be built. The entire project was carried out by volunteers.

The settlers soon realized that only through mutual assistance could they overcome their problems. At a meeting held in 1910, the 35-member Linda Estonian Farmers Association was founded with John Neithal as president, John Kerbes as secretary and John Oro as treasurer. Because local farmhouses were too small for the meetings that were held once a month, the idea of building a hall soon arose. The farmers donated the necessary materials and volunteered their labor. A new hall, spacious and simple, was ceremoniously inaugurated on St. John's Eve, June 24, 1911, barely one year after the founding of the association. The biggest gatherings each year were on St. John's Eve and Christmas. Parties with varied entertainment followed by dances were held frequently. Every month during meetings, while the older pleople discussed business, the younger ones played soccer or held choir and band practices. The proceeds from parties were used to establish a library, which grew to 2,000 volumes. A ladies' guild was active. This was a period of growth for the Linda settlement. People lived in harmony and the whole community inevitably attended weddings of christenings.

The Estonian settlement at Barons, in the grassy steppes of southern Alberta, 108 miles by highway from Calgary, was founded in the spring of 1904 when Jakob Erdman, born in 1853 in the Estonian township of Ambla, settled there with his family. Other Estonians from South Dakota, the Crimea and Estonia soon followed. The settlement grew quickly: by 1908 there were 77 Estonian settlers. Their main source of income was wheat, although other grains - even rye - were grown. When the market for wheat was poor, flax was cultivated because it was often easier to sell. Some Estonians raised horses. The most famous Estonian farmer in the area was Gustav Erdman. On his 70th birthday on April 8, 1956, the Lethbridge English-language newspaper published a lengthy article and photograph of him under the headline <<Still young at heart - Men like Gus Erdman, 70, built this land.>>

Despite the difficult climate all of the settlers prospered, especially after the building of the railway freed them from the necessity of hauling grain to town by horse-drawn wagon. In good years Gustav Erdman could sell 30 wagon loads of wheat, as well as rye, barley and oats. There were also hard times: crop failures, early killer frosts, sandstorms, plagues of grasshoppers and depressed markets. Mutual assistance saw the settlers through these trials. As well, the Estonian settlers at Barons were outstanding in their efforts at providing education for their children. Many of their sons and daughters obtained university degrees or specialized technical education and found good jobs, mostly in the city.

The first Estonian settlers at Foremost (40 miles south of Lethbridge near the town of Warner) came from the Koidu settlement in South Dakota. One of the first was Hans Meer (Maar), who had also been the first Estonian from the Crimea to emigrate to America. On August 31, 1907, he settled on 160 acres of land about 35 miles north of Warner. He was followed one month later by other relatives. By 1910, the settlement had seven Estonian families and two bachelor homesteaders. Over the years most, of the Estonian settlers have left the area.

The small town of Walsh is located about 30 miles east of Medicine Hat, only a few miles west of the Saskatchewan border. The Estonians who settled there came directly from Russia, the first, J. Smith, in 1904. He was soon followed by his parents and several other families. They settled about 10 miles south of Walsh where the land was empty and bare. As a result the early years were very hard, and those who could build a hut were considered lucky. Some had to settle for holes dug into a hillside until they could earn enough money to build a house. Walsh had 12 Estonian families, but after only a few years some left in search of better land. Estonians also lived elsewhere in Alberta, but detailed information about them is frequently lacking. Usually, isolated Estonian settlers became assimilated and lost their language in one generation because they had no contact with fellow Estonians.

Those Estonian settlers who managed to survive the Depression without losing their lands prospered. In addition to modern mechanicalagriculture, the oil industry changed the way of life in Alberta. Oil is produced in the vicinity of Estonian settlements at Medicine Valley, Stettler and Barons, and quite a few descendants of the Estonian pioneers work as petroleum engineers.

In the three other Western provinces there were few Estonians before World War I. The first Estonians in British Columbia were fishermen. Alec Pink came to Canada in 1895 and worked as a fisherman until later becoming foreman in a fish cannery. Losenberg from Pärnu arrived the same year and settled in the Finnish commune of Sointula on Malcolm island. At the turn of the century, other Estonian fishermen, a few forestry workers, craftsmen amd others aslo came to British Columbia.

The Masefield settlement in Saksatchewan was one desinination chosen in 1910 by Jaan Purask and his wife from Võrumaa. Only a few Estonians, widely dispersed over the province, came to Saskatchewan in this period. The first Estonian known to have come to Manitoba was Eduard Aksim, who according to the New York Estonian newspaper Estonian-American Post (Ameerika Eesti Postimees) was pastor of the German Lutheran congregation at Gretna, near the North Dakota border. A few years later the same newspaper published news of an Estonian called George Thomson in Manitoba.

In Ontario, the oldest and at one time the largest Estonian centre was the gold and silver mining town of Timmins. About 1905, Hans Krimbe from Saaremaa settled there and married a Finnish woman. He was followed by a number of others from Saaremaa, mostly single men. One of the Estonians, named Lepik, later became the Timmins chief of police. The Estonians worked as miners and, if the need arose, as woodsmen. They led an active social life with frequent get-togethers and larger parties. They would also help each other with joint projects such as house building and other endeavors requiring group efforts and developed close ties with the local Finnish population.

A few Estonians came to Ontario even earlier. According to the Estonian-American Post, an Estonian named Rudolfson came to Canada from New York in 1901 and went on to work in an iron ore mine. The same newspaper in 1906 published an article about a small five-person Estonian settlement at Wahnapitae. As well, a few Estonians had farms elsewhere in Ontario.

Due to Quebec's predominant Catholicism and French language, few Estonians in the province settled outside of Montreal. Several Estonians found short-term jobs in that city, such as Juhan Markie in construction. It is believed that the first Estonian to settle permanently in Montreal was Willem Kerson from Hiiumaa in 1912.

It's not known whether there were any Estonians in the Atlantic provinces before World War I.

Estonians in Canada during the Period between the Two World Wars

(Chapter 3, pp. 63-100)

During the years immediately following World War I Canada as an agricultural nation was moving toward industrialization as modern technology made its first impact. The world economic crisis known as the Great Depression, which showed its first signs in 1923, brought about a general slowdown in domestic and foreign investment, a decline in production and severe unemployment. The flow of immigration was therefore restricted by the Canadian authorities. Nevertheless some emigration from Estonia to Canada took place after 1924, largely due to adverse economic conditions in Estonia caused by the dislocations of World War I and the War of Independence, 1918-1920. Immigrants were channelled into agriculture in the Prairie provinces without regard for their skills or personal desires. There were no other opportunities for them in Canada.

The Estonian settlements in Alberta established before World War I had passed the pioneering stage and had prospered before the Depression. Newcomers began arriving from Estonia in 1924, reaching their peak in the period 1927-1931. They totalled 58, including 18 females. About 35 of them remained in the area as farmers but the rest moved on to cities and towns or to the Peace River area where they erected a sawmill and a flour mill. One Estonian almost singlehandedly established a 200-acre market-gardening operation. Others tried trapping and fur trading with limited success.

A noteworthy colonization attempt in British Columbia was led by Johan Pitka (Sir John Pitka), the former vice-admiral of the Estonian navy during the War of Independence. Pitka and his adherents believed that their services to Estonia had not been properly recognized and planned to create a new Estonia somewhere in North America. The admiral made some reconnaissance trips to British Columbia, being particularly attracted by the scenic Stuart Lake area. P'itka was 58 years old when in March 1924 he founded his settlement of 16 souls on the south shore of the lake across from Fort St. John. The settlers' attempts at agriculture and logging - using a portable sawmill - were not successful due to the inaccessibility of the area, which was served by only a seasonal road and far removed from prospective markets. In 1930 Pitka returned with his family to Estonia and the other settlers moved elsewhere in Canada.

Small vegetable, poultry or dairy farms were esablished by Estonian immigrants near Winnipeg, in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia and in Ontario. Some farmers worked in mines, lumber camps or in nearby cities to supplement their income. There were 12 small Estonian farms near St. Catharines, Ontario, and three in the Parry Sound area of that province. As well, small numbers of Estonians were involved in commercial fishing.

It was hard for unskilled men to find work. The women were better off because they could find jobs in hotels and as domestics. Those men who knew several trades often moonlighted -tailor by day, musician by night. Skilled tradesmen such as toolmakers became the elite among the immigrants. Some owned their own houses and automobiles. The homeowner enjoyed high standing among Estonians because his house could serve as a meeting place and provide shelter for recent immigrants. There were only a few Estonians with university educations in Canada. One of them was Professor Eduard Aksim, a theologian at the Lutheran seminary in Waterloo, Ontario.

The oldest Estonian organizations were in Alberta, where both the Medicine Valley Estonian Association (established in 1910) and the Linda Estonian Farmers Society (founded in 1913) owned community halls. The first urban organization was founded in Winnipeg in 1929 with a membership of 32. The founding of the Montreal Estonian Society took place in 1933. Elsewhere a group of Estonian women in Toronto formed the Club of Educated Estonian Women in 1931 to arrange lectures on Estonian topics and prepare exhibits for display at local high schools and community events. This club received first prize for a display of Estonian handicrafts at the Canadian National Exhibition in 1938. The club was also concerned with moral issues and advocated temperance. The Estonian musician Ludvig Juht, who played the double bass with the Boston Symhony, made his first solo appearance in Toronto in 1938 and convinced the local community that they should organize an association. As a result the Estonian Society 'Friendship' was established in 1939. During World War II the organization became fragmented and some patriotic Estonians left Friendship and in 1944 formed a new group, the Toronto Estonian Society 'Edu'(Progress). Its constitution declared that the new society's goal was to "unite Estonians to respect Estonian heritage and independence." When Estonian refugees came to Toronto after World War II this organization grew rapidly into the present-day Estonian Association of Toronto.

The interwar years coincided with the period of Estonian independence. Estonians in Canada maintained contact with the old country through correspondence and occasional visits to Estonia. The major cultural link was provided by newspapers, magazines and books published in Estonia. The magazine Meie Tee (Our Way), published in New York City, the major Estonian-American centre, included coverage of Estonian activities and problems in Canada. The Estonian consulate in New York also served Estonians in both countries. But visits by people from Estonia were rare. Bishop Hugo Rahamägi of the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church and the educator Jakob Westholm visited Toronto in 1931. Ironically, the internationally famous playwright and novelist Aino Kallas, who lectured at the Women's Canadian Club of Toronto, had no contact with local Estonians. Professors and scholars from Estonia made occasional visits to Canadian universities and institutes.

Estonians in Canada after World War II

(Chapter 4, pp. 101-125)

World War II severed all contacts between Estonians in Canada and their homeland. Even several years after the war no correspondence was possible with Soviet-occupied Estonia. With the collapse of the German front on Estonian soil in the summer of 1944 large numbers of Estonians fled to Sweden or Germany. But Sweden's postwar policy of friendly relations with , the Soviet Union provided the impetus for many Estonians to leave that country in order to be as far as possible from the grasp of Communism. War-torn Germany was likewise a place which every refugee tried to leave as soon as possible and at any cost. But because Canadian immigration policy saw in the displaced persons of the German refugee camps nothing but a half-starved disintegrated horde, it was inconceivable that they could be useful immigrants for anything other than manual labor. As a result, a large proportion of immigrants with potential for managerial and professional positions were "buried" for at least one year in Canadian forests, farm fields or in domestic servfee. The opportunities for immigration to Canada from the German displaced persons camps and from Sweden through the Canadian consular authorities improved somewhat around 1948-1949. Those refugees who went to Great Britain from Germany later emigrated in large numbers to Canada.

A separate chapter in the history of Estonian immigration to Canada was written by the "boat people" who arrived on the "Viking ships", small vessels which often lacked proper navigation equipment. Between 1945 and 1950 10 ships carrying a total of 1,127 refugees arrived in Canada from Sweden. In addition, 3 ships from other countries brought 466 persons. According to available information, though 50 Estonian Viking ships left Europe in search of new homelands and many were lost at sea. The arrival of the Viking ships was proof that if hundreds of people were ready to brave dangers and even death they must have faced a greater evil than death itself: Communism. In fact Canadian immigration authorities treated the boat people as political refugees.

The Estonians' first jobs in Canada were mostly temporary and involved manual labor: forestry, mining and large hydroelectric construction projects. This led to many Estonians working together. For example, a group of labores near Longlac, Ontario, including two Estonian university graduates and 11 Estonian university students who later rose to prominent positions in their professions. Forestry was not exclusively a "male occupation, as Estonian women worked in the camp kitchens. About 25 Estonian women held such positions in the Lakehead region of Ontario.

One of the largest employers of Estonian refugees from the camps of Germany was Ontario Hydro, which recruited workers for construction of the dam and hydroelectric generating station at Rolphton, Ontario, on the Ottawa River. These Estonians formed the Rolphton Male Choir, which gave several concerts both locally and in Montreal, Ottawa and various northern Ontario centres. The Rolphton project was to last three years, which meant that many workers established more permanent homes. Dependents still in Germany were allowed to immigrate only if suitable accommodation had been established. To meet this need the Estonians built a settlement called Virola at Rolphton, housing 42 residents at the time the project ended in 1951.

After fulfilling the requirements of their immigration agreements, the Estonian refugees generally tended to move to larger cities, where employment opportunities were more diversified. The shortage of rental accommodation forced them to invest their savings in housing. Financial problems, language difficulties and adjustment to the new environment caused hardship and crises in the life of the immigrant. Nevertheless Estonian immigrants became acclimatized fairly rapidly and generally became equal and energetic partners in Canadian economic and social life.

In the eyes of the newcomer, Canadians appeared easely approachable, honest and less formal than Europeans; on the other hand, Canadians seemed somewhat indifferent in comparison with Americans. In the early stages the integration of immigrants took place only through the economic process, not through social or cultural activities. But in church and religious matters Canadians were always warmly receptive and willing to assist, and this provided the basis for congregations with Estonian-language services and later Estonian church buildings. The first political relations of a more permanent nature with Canadians arose with the founding of ethnic newspapers. The early attempts by educated Estonians to make contact with Canadian universities and institutions of learning were more modest.

The Estonian refugees who came to Canada after World War II were greeted by older Estonian settlers who had immigrated here before World War I or in the interwar period. Contacts with them generally remained on a strictly neutral basis for a time. Politics was avoided; often the reason for the earlier arrivals' immigration had been the difficult years of economic dislocation in Estonia, and their political views were influenced by Canada's foreign policy, which had been friendly to the Soviet Union. It took some time before the gulf of several decades could be bridged. The pre-World War II settler had to accept something dramatically new. Estonian-language church services, choirs, dramatic productions, newspapers and youth organizations were startlingly novel to them and had been impossible under the old scheme of immigration. Generally the prewar Estonian settlers have been of great assistance to the newcomers. Their contribution to the establishment and initial direction of many local Estonian organizations has been considerable.

Estonian social and political life in Canada initially seemed be focussed in Montreal in the period 1947-1950. The local Estonian community had grown to about 1,500 by 1950 and then began to decline as the centre of Estonian activities shifted to Toronto, which offered much better employment opportunities, especially in manual occupations. Hundreds of houses in Toronto were built by Estonian tradesmen. The first Estonian weekly newspaper Meie Elu (Our Life) was founded there in 1950. The organized community in Toronto, with its own associations, newspapers, congregations and businesses was a magnet for Estonians arriving to Canada.

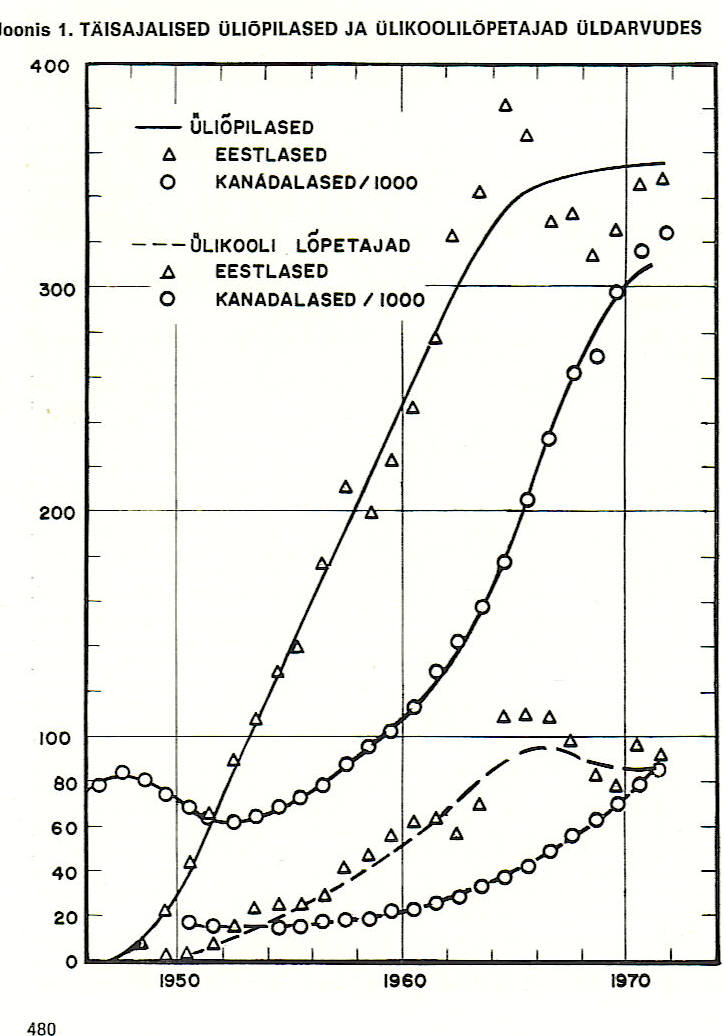

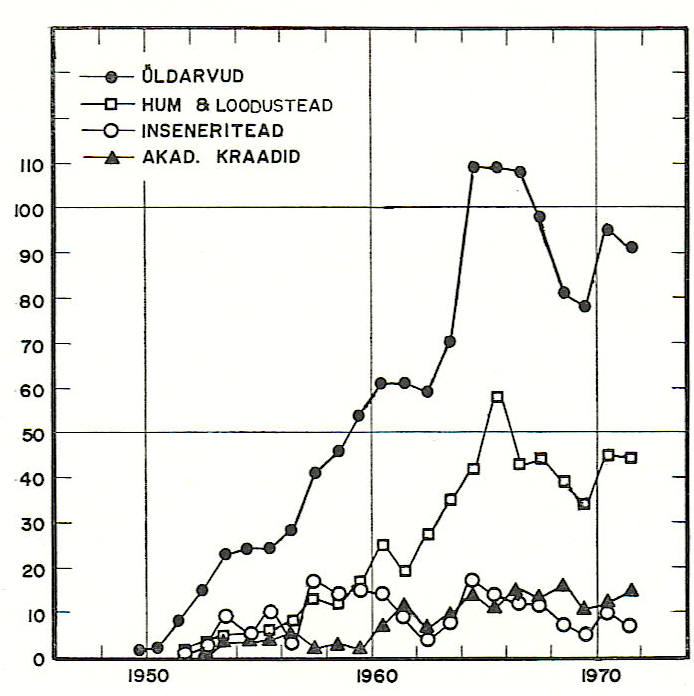

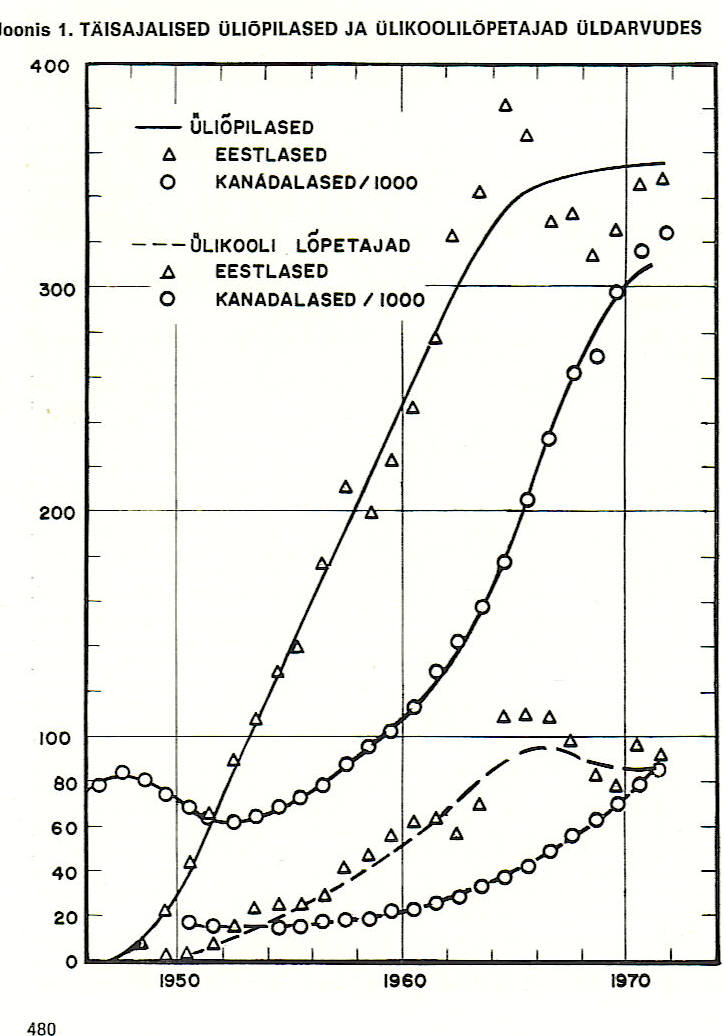

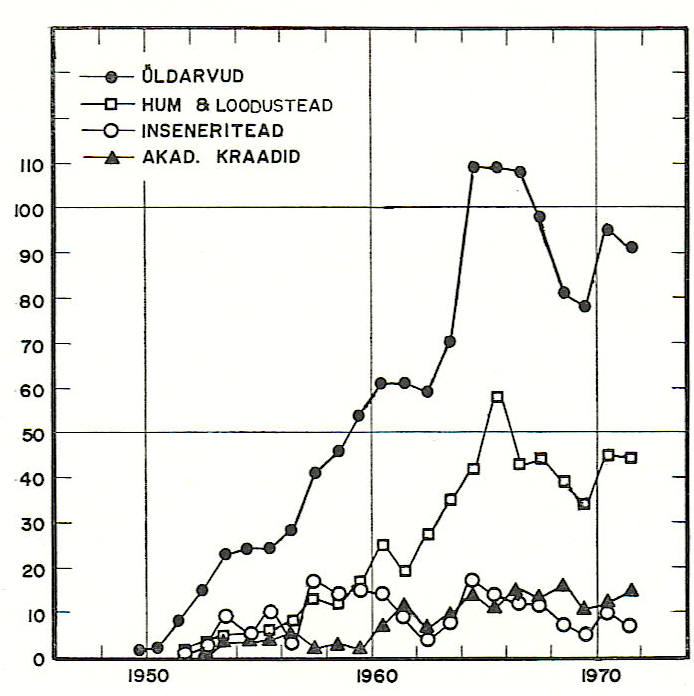

Analysis of a sample group provides a limited but interesting picture of Estonians in Canada. The 1961 census disclosed that almost 19,000 Estonians then lived in this country, although only a fraction responded to a questionnaire distributed by the Canadian Estonian History Commission. The questions on education were answered by 1,565 persons as follows: those with elementary education numbered 176 (9 percent); secondary education 738 (49 percent); vocational or military education 197 (13 percent); and higher education 454 (29 percent). The percentage of university graduates in this group is artificially high, i.e. the group under consideration is not in all aspects representative of the Estonian community in Canada. The latter group actually forms about 8 percent of total Estonian population in Canada.

Information on annual income was obtained from 1,181 individuals. Their income in 1965 was: up to $5,000 annually, 723 persons or 61 percent; more than $5,000 annually, 458 persons or 39 percent. Of the latter, 113 persons (10 percent) earned more than $10,000 annually. The section on real estate and business was answered by 1,619 persons. Homeowners numbered 905, 299 owned cottages and 77 owned farms. Information was supplied on 30 commercial establishments and 29 industrial operations. Considering the small size of the Estonian ethnic group, its contributions over a short period of time to the Canadian economy have not been insignificant.

Eastern Canada

(INCLUDING THE ATLANTIC PROVINCES, QUEBEC AND PART OF ONTARIO) (Chapter 5, pp. 126-131)

Newfoundland's small Estonian population, mostly composed of those transferred there on specific assignments, has declined over the years. The 1961 census showed 108 Estonians in Newfoundland, 55 men and 53 women. Ten years later their numbers had fallen to at most 20, concentrated in St. John's and at the hydroelectric projects of central Labrador. Prince Edward

Island had an Estonian population of six in the 1961 census, two men and four women.

A group of Estonian women came to Nova Scotia in 1948, recruited from Germany to work as domestic servants. When their contracts expired some remained in Halifax and found new jobs, while others went elsewhere. In 1948 groups of Estonian refugees from Sweden began arriving in Nova Scotia as boat people on board what were termed Viking ships. The largest vessels were the Pärnu with 150 refugees, the Walnut with 347 and the Sarabande with 253. Because the Estonian boat people had no immigration visas, they were detained for a few months, but later were free to find jobs anywhere in Canada. According to the 1961 census there were 157 Estonians in Nova Scotia, 85 men and 72 women. By 1971 their number had declined to 54. There are no Estonian organizations and social activity is minimal. The pastor of St. John's Estonian Evangelical Lutheran congregation in Montreal has arranged church services in New Glasgow, which have been followed by social gatherings. There are also a few Estonians who work as commercial fishermen in Halifax, Lunenburg and elsewhere.

The Estonian population of New Bruncwick was 106 (50 men and 56 women) according to the 1961 census. They are concentrated in the largest citly, Saint John. The large proportion of physicians among them is noteworthy. By 1971 the Estonian population had declined to 37.

Quebec had an Estonian population of 1,546 (716 men and 830 women) according to the 1961 census. Montreal and its suburbs were estimated in 1967 to be home to about 1,080 Estonians: 333 families and 217 single adults. The largest group of cottages owned by Estonians, at Dalesville, 48 miles northwest of Montreal, totalled 36 summer homes in 1968. Many others have cottages on Lake Champlain rnear the United States border. Another cluster of about 10 cottages is located on Blue Lake in the Laurentians. In 1948 a group of Estonians from the German refugee camps obtained employment as domestic and hospital workers in Sherbrooke, 96 miles east of Montreal. The were joined in1949 by a group of 46 skilled textile workers from Sweden. At theend of 1949 there were 80 Estonians in Sherbrooke. By 1971 only 26 remained.

Those Estonians who lived in the vicinity of Cornwall, Ontario, have moved to Montreal or to the west. There are still two Estonian farms and a few families in the area. Kingston, Ontario, has about 30 Estonians, not including students at Queen's University and the Royal Military College of Canada.

Montreal

(Chapter 6, pp. 132-148)

There is no record of when Estonians first arrived in Montreal, although it is generally assumed that seamen intermittently wintered there. The first known Estonian resident of Montreal, Villem M.. Kerson, jumped ship in 1910 after four years at sea, went to Ontario and two years later moved to Montreal. By 1930 a sizable Estonian community composed mostly of young, single people had been established in the city, and in 1933 the Montreal Estonian Society was founded. The association was active until the outbreak of World War II, when many young men entered military service or moved to the United States or elsewhere in Canada.

A renaissance in the Montreal Estonian community began in 1947, and during the next three years the Estonian population grew to more than 1,500 from about 300. Despite the new immigrants' limited knowledge of English or French, those with technical training were in great demand in the Montreal job market. By the end of the 1960s there were about 650 Estonians in the Montreal labor force, employed chiefly in manufacturing, commerce, banking and insurance. Most Estonians in Montreal live in the western part of the city and in the suburbs of the West Island. Their favored summer cottage areas are Blue Lake, Dalesville and the Lake Champlain area. The largest and most memorable event organized by Montreal's Estonian community was the very successful day of festivities and performances held at Expo 67 on May 21, in which more than 600 performers and 3,000 spectators took part.

The Montreal Estonian Society, which lay dormant during World War II, was reactivated on January 28, 1948. The increased flow of Estonian immigrants during the early 1950s provided the vitality to support a wide range of cultural endeavors. The society has cooperated with other organizations to hold art exhibits and ceremonial gatherings on Estonian national holidays.

The second oldest Estonian organization in Montreal is the St. John's Estonian Evangelical Lutheran congregation. Established on January 9,1949, the congregation has been served since its inception by Pastor Karl Raudsepp. In 1954 the congregation bought a church on Marcll Avenue in the western part of the city, which ,was consecrated on November 7 of that year and has since become the centre of community activities. At the end of 1971 the congregation numbered 921. Of other congregations, the St. Paul's Estonian Evangelical Lutheran congregation of Montreal, founded on October 17, 1954, is served by Rev. Oskar Gnadenteich and the Estonian Orthodox congregation, founded in November 1954, is headed by Archpriest Mihkel Ervart.

The Montreal Estonian Women's Choir was founded in 1949 and later became the Montreal Estonian Mixed Choir. Although that choir was disbanded in 1961, in 1964 the women's choir recommenced its activities. The Montreal Estonian Male Choir was founded in December 1954 an gave its first full-length concert in April 1956. The Montreal Estonian War Veterans Association, which has devoted itself to the relief of disabled veterans, was founded in February 1952.

The first Estonian boy scout troop Kotka was founded on January 21, 1951, and as membership grew it became the Estonian Kalev troop in 1952. The first girl guide group, formed in November 1951, developed into the Virve company a year later. In 1957, the Montreal Estonian Youth Relief Association, founded in 1952, purchased a suitable site for a boy scout and girl guide camp in Dalesville. Parcels of this property were sold to private individuals, forming a village of about 20 summer cottages.

Although there has been no independent folk-dance company in Montreal the first group of enthusiasts was active as early as 1949. In 1963, the folk arts ensemble Vikerlased was formed as a joint venture of the boy scout and girl guide movements. It ceased its activities in 1970 when the director and music director both moved to Toronto.

The Montreal Estonian supplementary school began in conjunction with the Sunday school in 1949. Since 1954 classes have been held in St. John's Church. The Montreal Estonian Sports Club was founded in 1952. Both the men's and women's volleyball teams have achieved considerable success, and the women's team won the Canadian championships in 1954 and 1955. The Estonian Women's Association of Montreal was formed in 1958. Since then, the association has featured more than 90 presentations on a wide variety of topics at its meetings. The number of Estonians in Montreal who belong to student fraternities and organizations exceeds 200. The various groups jointly hold an annual Alma Mater Day assembly, where prizes are awarded to the best entrants in the student essay competition.

Ottawa

(Chapter 7,pp. 149-154)

A few Estonian immigrants settled in Ottawa around the turn of the century, among them Juhan Markie, who was 22 when he arrived from Estonia in June 1907 with his two nephews. The number of Estonians increased substantially after World War II. The first of this wave were groups of young Estonian women from Germany hired as household servants in 1947. A few well-educated professionals from the refugee camps in Germany followed and obtained civil service positions. The Ottawa Estonian Society (OES) was founded on December 12, 1948, and began an active program of cultural and social activities. Close contacts with the Department of Citizenship and Immigration helped solve many problems.

In cooperation with the Latvian and Lithuanian communities, Ottawa Estonians publicized the plight of the occupied Baltic countries and their peoples among Canadians. Members of Parliament and government representatives delivered addresses at commemorative assemblies to mark the mass deportations from the Baltic nations. According to available statistics the Estonian population in Ottawa numbered 138 adults and 17 children in 1957. Religious activities became organized in 1961 with the founding of St. Paul's Estonian Evangelical Lutheran congregation, which worships at St. Paul's Lutheran Church and at its peak numbered 100.

In 1959 the president of the OES called a meeting of representatives from European groups, which led to the formation of the League of Captive European Nations. Due to protests from this organization, the mayor of Ottawa cancelled a proposed meeting with the mayor of Moscow. The league's objectives are to counter Communist propaganda and to demonstrate support for those who speak out in defence of the occupied nations of Europe, such as Prime Minister John G. Diefenbaker who in an address at the United Nations in 1960 demanded freedom for the Baltic republics and other captive nations.

Over the years the number of Estonians in Ottawa has fluctuated, with resulting variations in the level of activity. Despite the small size of the community the work of the OES and the congregation has continued without interruption. The OES organized a theatre group which in 1968 mounted a very successful production of Oskar Luts's Pärijad (The Heirs) that was also staged for the Estonian community in Montreal.

In 1971 there were some 140 Estonians in Ottawa, many of them retired public servants. Almost all families are homeowners and many have cottages at scenic Crown Point, 35 miles west of the city.

Toronto

(Chapter 8, pp. 155-173)

Toronto's Estonian population of 10,000 is distributed throughout the metropolitan area. Those Estonians who settled there were well qualified vocationally and educationally. Many worked at odd jobs at first due to language difficulties, but over the past 20 years their achievements have been substantial. Estonian House, the focus of Estonian activities and home to many organizations, is their greatest accomplishment. The idea of acquiring a community centre first arose in 1954, and an organizing committee was formed three years later. A vacant school on Broadview Avenue in East York was bought in 1960 and an addition built in 1962. The Estonian House in 1975 housed the Estonian Association of Toronto and its kindergarten and supplementary schools, the Estonian (Toronto) Credit Union, the Estonian Central Council in Canada, The National Estonian Foundation of Canada, a gift shop and the Estonian Central Archives in Canada.

The oldest existing organization is the Estonian Association of Toronto, founded on November ,18, 1949. 1951 witnessed the establishment of the first children's summer camp, with 100 participants. The supplementary school began its program of evening classes in Estonian language, history and music in 1952. Such groups as the Hunters'and Anglers' Association, the folk-dance troupe, the literary circle and others that later became independent were formed under the aegis of the association. The women's section of the association purchased a farm at Udora and established a children's summer camp before becoming a separate entity, the Toronto Estonian Women's Association. The supplementary school's enrolment grew from 367 in 1955 to more than 500 in 1971. A nursery school section was established when the school moved to the Estonian House in 1960. The association also opened a library, with 1,260 volumes. The Estonian Philately Association was founded in 1955. The Estonian Agronomists' League established on March 4,1954, has organized lectures and field trips to agricultural and horticultural establishments and the University of Guelph. The activities of the Economics Club, founded in 1966, consist of lectures and seminars on economic issues. Those Estonians who come from the island of Saaremaa formed their own association in 1956, and published a commemorative album. The various student associations and fraternities which functioned in independent Estonia have continued their activities in Toronto. An alumni association was founded in 1966. Veterans of the Estonian regiment that fought in Finland formed an association in 1950. The Toronto Estonian Senior Citizens' Club, founded in 1970, has been expanding rapidly. The club - which has its own library - organizes social gatherings, excursions and numerous other activities. The Toronto Estonian Garden Club, formed in 1970, holds lectures discussion groups, film presentations and field trips.

The Estonian Male Choir of Toronto was founded on October 7, 1950. It has performed in Canada, the United States and Europe. 1951 saw the formation of both the Toronto Estonian Mixed Choir and the Toronto Estonian Women's Choir. The youngest choir is the youth mixed ensemble Leelo, founded in 1965. The Estonia concert band was formed in 1956. Eight voice and piano teachers serve the musical needs of the community. Theatre groups have been active since 1950; the first, the Estonian Actors in Canada, was followed the Estonian National Theatre in Canada, established on November 4, 1951. Since 1955 more than 50 plays have been staged in Estonian at the Eaton Auditorium, not to mention many open-air performances and other productions.

The largest athletic group is the Toronto Kalev, founded on April 24, 1951, whose activities have included soccer, basketball, track and field, women's rhythmic gymnastics, men's and boy's gymnastics, cross country skiing, tennis and swimming. Special mention must be made of the internationally acclaimed women's gymnastics group Kalev Estienne, which has appeared at Expo 67, the Mexico City Olympics in 1968, the royal visit of Queen Elizabeth II in 1967 and Expo 70 in Japan. The Tiidus gymnastics group, founded in 1949, also promoted women's gymnastics in Canada. As well, scout and guide organizations have played a major role in shaping Estonian youth.

Until 1969 Johannes Markus served as consul of the Republic of Estonia in Toronto. After his death, llmar Heinsoo was appointed honorary consul general. For many years the Estonian Central Council in Canada, a democratically elected body representing Estonians from across Canada, has stood at the forefront of representing Estonian-Canadian interest. Political matters are also the concern of other political oriented organizations.

Eight Estonian congregations serve the spiritual needs of the community. Two of them, St. Peter's Estonian Evangelical Lutheran congregation and the Estonian Baptist congregation on Broadview Avenue, have built modern churches. St. Andrew's Estonian Evangelical Lutheran congregation has for more than 20 years used Old St. Andrew's Church at Carlton and Jarvis, bought jointly with a Latvian congregation.

Since the 1950s the newspapers Our Life and the Free Estonian, published in Toronto, have served as sources of information on community life. Estonian periodicals and books are printed at Ergon Type, Oma Press and Estoprint, all of them owned by Estonians. There are also many Estonian-owned industrial and commercial establishments in Toronto. The number of Estonian physicians, engineers and other professionals is considerable.

Estonians in Southern Ontario

(Chapter 9, pp. 174-194)

Only about 100 to 150 Estonians lived in southern Ontario before World War II, most of them farmers or employed in various skilled occupations. After the war a large proportion of the new Estonian immigrants to Canada came to this area, drawn by the sponsorship of Estonians already living in the region, assistance from the Lutheran Church, job opportunities and the geographic location. Soon, however, many of them moved to Toronto where employment prospects were better. A majority of the newcomers became employed in industry or service occupations, and after a period of adjustment many of them have advanced into supervisory and managerial positions. Since the mid-1950s the Estonian population in southern Ontario has remained stable, in 1975 centred in four cities and their surrounding areas: Hamilton-Burlington, with 800 to 1,000 Estonians; Kitchener with 150 to 200; London with 200 to 250; and St. Catharines (together with Niagara Falls) with 400 to 600. After graduating, young Estonians have mostly moved away, but conversely many from elsewhere have found employment here in managerial, teaching and other positions.

In each of the four main centres an Estonian'society was founded in 1949 or 1950, leading to the development of choirs, folk dance, boy scout and girl guide troops, and various special-interest clubs. The vigorous local ethno-cultural life was often enriched by cooperative ventures with other centres including Toronto. The Ontario Estonian summer festivals from 1949 to 1952 took place in the Hamilton-St. Catharines area. Estonian congregations were also founded, except in Kitchener which joined the Estonian church in Hamilton. Supplementary schools were established in all four centres to teach children Estonian language and history; summer camps and sporting events were organized. Commemorative assemblies to mark the anniversary of the 1941 deportations from the Baltic states, held jointly with the Latvian and Lithuanian communities, and participation in local multicultural activities became regular features, A pattern of annual events took shape: Estonian Independence Day in February, Mothers' Day in May, two annual parties with comprehensive cultural program (spring and fall), a Christmas gathering and sometimes a New Year's Eve party.

In general, this pattern continues to the present day. However, the frequency of activities and the level of enthusiasm have declined noticeably, especially because young people have left the area and newcomers do not join or assume leadership roles. Still, in Hamilton - the largest centre - a rejuvenation of the leadership has taken place. The choir which claims about 30 to 40 members. In addition to sizable folk dance and scout troops and a viable veterans' association, a well-known youth choir has recently emerged. The supplementary schools continue with remarkable regularity except in Kitchener. Estonian university student associations exist in Hamilton and Waterloo, the latter uninterruptedly since 1960 despite an inevitable turnover of members every few years. The combined membership of the four Estonian societies has been about 400 to 600, the enrolment in supplementary schools from 60 to 70, with about 50 to 60 scouts and guides. The societies have libraries of several hundred voluroes each.

The collective achievement of southern Ontario Estonians has been Seedrioru, which originated as a children's summer camp. That remains its primary purpose. Having found separate summer camps impractical and expensive, the four societies jointly purchased a 62-acre farm near Elora on the-Grand River in 1955. Many years of unpaid volunteer work has resulted in the beautifully landscaped grounds, modern central hall, three camp dormitories, a sauna, an outdoor swimming pool, an open-air theatre complex and an artistically designed monument to Estonians who fell in many wars. More than 54,000 man hours of volunteer work have been devoted to the project, in addition to administrative duties. Though much was done without remuneration, funds were needed to pay the mortgage and purchase building materials. This led to the summer festivals, which have been held annually since 1956. The programs have included song festivals, folk-dance and gymnastics presentations, concerts and open-air theatre performances, among them a production of Hamlet in Estonian in 1963. Seedrioru has attained the rank of a major cultural centre. The average attendance has fluctuated between 2,000 and 3,000, including large numbers of Estonians from the United States, and a record of 8,000 was set in 1972. The proceeds have been used to retire all debts completely and to meet the operating expenses of the summer camp.

Northern Ontario and Manitoba

(Chapter 10, pp. 195-203)

The major centres of Estonian settlement in Manitoba and northern Ontario includes Winnipeg and its environs, the northern Ontario cities of Thunder Bay, Sault Ste.Marie, Sudbury, North Bay, Timmins and Kirkland Lake, and a number of smaller communities in the northern Ontario gold-mining belt. These areas offered employment primarily in agriculture (Manitoba), forestry (centered on Thunder Bay) and mining (northeastern Ontario).

The first known Estonian settler in the Winnipeg area was John Pressmann, who began farming near Portage la Prairie in 1905. A large group of single men came in 1928-29 under contract to the Canadian Pacific Railway. They were required to work for one year as farm laborers, after which they were free to find employment on their own. At the same time Hans Krime in Timmins became the first Estonian to reach northern Ontario, and was soon followed by many others.

The massive influx of Estonians to Manitoba and northern Ontario began in 1947, and was composed mostly of refugees from the displaced persons' camps in Germany. Because the Prairie provinces needed farmhands, the Estonian population in Winnipeg and vicinity quickly grew to some 200. Estonians in northern Ontario numbered about 1,800 to 2,000 in 1951. To ease the process of acclimatization and to preserve their heritage, Estonians in all of the larger centres formed Estonian associations and later other activity groups and church congregations.

The Winnipeg Estonian Society "Side" was founded in May 1929. Among its activities were a theatre circle, a folk-dance company, a male choir and a youth group. In 1969 a revitalized mixed choir came on the scene. An Estonian newspaper, the Winnipeg Estonian Reporter, began publishing in 1957 and survived for a few years.

The Port Arthur Estonian Society was founded in 1948, followed by the Port Arthur Estonian Evangelical Lutheran congregation a year later and the local mixed choir in 1950. Among other things the society oversees the activities of the supplementary and Sunday school and the folk-dance company. In cooperation with the congregation a farm property named Sillaoru was acquired in 1957. The largest event was the Central Canada Estonian Summer Festival in July 1965 with 500 participants.

The Kirkland Lake Estonian Society was formed in 1949. By 1953, the community was composed of 200 persons, principally miners and their families. The society organized interest groups in athletics, folk dance, chess and checkers and a male choir. A supplementary school and a social relief committee were also active.

The Sudbury Estonian Society was founded in January 1952, when more than 100 Estonian families lived in the city. The society has supported a supplementary school, a folk dance company and an energetic theatre group. The Sudbury Estonian Evangelical Lutheran congregation ministers to the religious needs of the community.

The Sault Ste. Marie Estonian Society was organized in October 1957. Local activities overseen by the society include a supplementary school, a folk-dance company, a mixed choir and a women's gymnastics group. The society also owns a summer campground, which was inaugurated on August 10, 1969.

Alberta and Saskatchewan

(Chapter 11, pp. 204-214)

During the years 1947-51 European refugees, including Estonians, were permitted to come to Canada under one-year labor contracts primarily in agriculture on the Prairies. Between 1948 and 1954 more than 50 Estonians came to Eckville, Alberta, and more than 60 were sponsored by Estonian settlers in the Barons area of southern Alberta. At first the new immigrants found jobs on farms owned by Estonians and in the sugar beet fields in the Lethbridge area, although many soon moved to Edmonton and Calgary.

Both Edmonton and Calgary had about 60 known Estonian residents at the end of 1949, including pre-World War II immigrants. According to the 1966 survey, there were 87 Estonians in Edmonton, while the community in Calgary had grown to 120. In the early 1950s Lehtbridge had up to 30 Estonians, Barons 50, and Eckville 80. Estonians were also found near Stettler and a few lived in the Peace River county and elsewhere. The total number of Estonians in Alberta was probably around 400.

Social contacts among Estonians shortly after their arrival in Alberta communities were very intensive and soon took on a more organized form. The Edmonton Estonian Society was founded in October 5, 1949. The society formed at Barons on August 21, 1949, had two sections, one in Barons-Lethbridge and the other Calgary. The latter became the Calgary Estonian Society in June 17, 1950.

The Medicine Valley Estonian Society, founded on April 24, 1910, near the central Alberta town of Eckville, was still active. It had been temporarily dormant from 1944-48, but the situation changed dramatically in 1948 when Estonian refugees began to arrive in Medicine Valley. Many of them joined the society and gave new life to its activities. The vitality of the 1949-56 period faded quickly as most of the newcomers and younger Estonians left for larger centres.

From 1948, the Medicine Valley Estonian Society invited Estonians from other parts of Alberta to participate in its traditional summer festival. This laid the foundation for the 1951 Alberta Estonian Festival, which became an annual event in Eckville, except for the 1954 festival held in Edmonton.

The Estonian associations of Alberta were also actively devoted to publicizing Estonian achievements through Canadian newspaper interviews and radio programs. A large-scale commemoration of Estonian Independence Day together with an exhibition took place in Edmonton on February 24, 1950. One of the most significant events in Calgary was a ceremonial assembly and concert to mark Independence Day on February 21, 1954.

In both Edmonton and Calgary Estonians have been in close contact with the local Finnish, Swedish, Lithuanian, Latvian and Polish communities, jointly organizing craft shows, festivals and social gatherings. The mass deportations from the Baltic republics have been marked by memorial assemblies sponsored by the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian communities. The largest joint event was the Baltic Festival held in Edmonton on October 6-7, 1967, which included a concert, an exhibition, a gala reception and a banquet attended by government representatives.

Estonians in Alberta have also shared in the wealth generated by the rapid economic expansion based on oil. At the beginning of the 1970s there were 13 Estonians, mostly independent entrepreneurs, in the construction and furniture sectors in Calgary, where many were also employed as engineers, technicians, draftsmen, journalists, managers and administrators. In both Calgary and Edmonton there are many Estonians on university faculties and in public service.

The educational level attained by young Estonians in Alberta has also been high. No fewer than 13 school teachers trace their ancestry to a small group of early Estonian settlers in central and northern Alberta. The percentage of university graduates has also been high in comparison with the Canadian average.

There have never been significant numbers of Estonians in Saskatchewan. The 1961 census showed 150 Estonians widely dispersed throughout the province. There are no Estonian organizations in Saskatchewan and social events take place only on a family basis.

British Columbia

(Chapter 12 ,pp. 215-231)

World War II had been over for more than two years when the first Estonian refugees from Communism began to arrive in British Columbia Until then there had been fewer than 100 Estonian families in the entire province. By 1951 their numbers had reached 876, growing to 1,986 in 1961. The newcomers brought new vitality to the social life of the Estonian community. As early as November 6, 1948, they formed the Vancouver Estonian Association, which united both earlier immigrants and postwar refugees. Their first major event was a gathering on Christmas Day, 1948, at Hastings Auditorium. Since then a wide variety of social events have been held at different times of the year. The commemoration of Estonian Independence Day on February 24 has become an annual tradition.

Folk-dancing, choral music, women's gymnastics, Estonian-language theatre and an Estonian supplementary school have been among the activities of the Vancouver Estonian Association and the specialized organizations that have developed under its direction. Estonians became well known in the world of sports in British Columbia when an Estonian team won the provincial championship in volleyball several times. As well, Estonians in the Pacific Coast region hold a biennial festival that brings together people from California to British Columbia and beyond. The West Coast Estonian Festival has been held in Vancouver in 1961, 1969 and 1977. Estonian-language radio programs have been produced in Vancouver on cultural and religious themes, the latter being broadcast regularly each Sunday since 1962. And together with the Latvian and Lithuanian communities, Estonians have organized political demonstrations to protest against Soviet imperialism and Communist brutality.

During the 1950s plans were made to purchase or build an Estonian house, but these did not materialize because other, perhaps more urgent projects were pursued. Estonians have been very active church builders in Vancouver. The different denominations have constructed three churches of considerable size, the most prominent being the high-roofed church at Oak Street on 49th Avenue. Most of the community's cultural activities take place in a hall adjacent to the church, which for all practical purposes is the Estonian House of Vancouver.

Because forestry is British Columbia's primary industry, it provided the first jobs for many Estonian immigrants. A large number worked as loggers on the coast and on Vancouver Island. Some bought their own power equipment, hired men to run it and worked as logging contractors for various lumber companies. A few Estonians established their own companies, selling logs and lumber. Estonian engineers took part in the design and supervision of construction of the Kemapo hydroelectric station in the early 1950s. Estonian loggers and laborers worked on clearing the power lines around Kemano and at the Kitimat townsite. Some of the loggers were later employed by an Estonian contractor to clear the forest for the power lines at Woodfibre, a gas pipeline at Hope and a railway line at Pine Pass.

More than anywhere else, the Estonians left their mark in home and apartment construction in Vancouver and Victoria. In the late 1950s there were close to 40 Estonian contractors in Vancouver. In the past two decades about 1,400 houses with a value of $29 million were built by Estonians in Vancouver. As soon as the more successful contractors had acquired the necessary working capital, they undertook larger construction projects, completing about 3,600 apartment units in Vancouver and 436 in Victoria. Also, an Estonian businessman built a motel and golf course at Pitt Meadows. The ready-mix concrete trucks one sees in Vancouver bearing the name Kask Bros, belong to a company that was established by Estonians. One Estonian formed a boat-building business whose products were widely displayed at Vancouver shows.

Many Estonians have been remarkably successful in the field of higher education. At a time when few women attended Canadian universities, Marie Gerhardt-Olly, a cofounder of York House School, completed her Masters of Philosophy at the University of British Columbia in 1932. Since then about 100 Estonians have graduated from UBC. Four professors educated in Estonia were members of the UBC faculty in 1949.

Roots of the Estonian Heritage

(Chapter 13, pp. 235-244)

By origin Estonians are a Finno-Ugric people. In actual fact, though, the Estonians of today are of mixed background like all other nationalities. Nordic characteristics predominate in the coastal and island regions, while in the interior of Estonia the population displays many eastern Baltic features. Estonians have demonstrated both at home and abroad their exceptional industry, initiative, their aspirations towards spiritual and intellectual ideals, their persistence and their sometimes excessive obstinacy.

Environmental and social factors have been far more important than genetic ones in shaping the Estonian character. It is believed that the basic determinants of Estonian character traits was their distant forebears' life in the rough environment of the forests and coasts of northern Europe. Such a milieu favored the development of industry, patience, tenacity, caution and a sense of beauty. The desire to conquer others is absent, as it is among the Finns. For this reason the more aggressive Slavic peoples have constantly expanded into the areas of the Baltic Finnic nations. At present Estonia is under Soviet occupation, which has destroyed much of its material and spiritual heritage. The survival of the Estonian people has become the primary question for all Estonians at home and abroad.

How well adjusted were the ancestors of the Estonians? Maternal love and the role of the father in shaping the intellect are strong motifs in Estonian culture. On the other hand, old documents and folk traditions show that their lives were also marked by tribulations and internal tension. The difficult external conditions of which Estonian history speaks undoubtedly influenced personal, family, and social life in the internal sense. It is difficult to say to what extent Estonian character traits have been influenced or determined by psychological factors.

A further question is what effect the immigration process exerted on Estonians in Canada. It may generally be stated that in coming to a new country, people torn from their roots are in particular need of support from their fellow countrymen, with whom they are united by many common needs and characteristics. Through mutual aid, both psychological and material, it is easier to begin life in a foreign land. Some scholars have noted that those who are supported by their own ethnic group develop better relations with the majority nationality. Because the level of social activity among Estonians in Canada has been exceptionally high, it cannot be said that Estonians have not become well integrated into Canadian life. The majority have done well financially. There are Estonian organizations which have linked them more closely with Estonian cultural, political and social activities.

The major problem facing the Estonian community is that of an aging population. Most of those who came to Canada after World War II were middle-aged and have now grown old. Their children and descendants are fewer in number and separated by distinct demographic gaps. For this reason the younger generation has not yet been able to play a major role in the life of the community. Nevertheless, the level of activity among young Estonians in the major centres is quite high. In the smaller centres across the country, though, one can detect assimilation into the mainstream of Canadian culture.

National organizations

(Chapter 14, pp. 245-294)

During the first few years of Estonian immigration to Canada after World War II the centre of Estonian social and political activity was Montreal. In the early 1950s, with the massive arrival of Estonian refugees from Sweden and Germany, Toronto became the focal point of the community, which was now large enough to allow for the formation of major organizations.

The Estonian League of Northern Canada

On June 6, 1946, the Northern Ontario Estonian Brotherhood was founded in Mattawa. This political organization, later known as the Estonian League of Northern Canada, hoped to draw into its ranks a large proportion of the almost 1,000 Estonians who worked in the area. In fact, membership never exceeded 140 and activities ceased in 1952.

The Estonian Federation in Canada

In 1949 there were 15 local Estonian societies in Canada. These groups, founded by prewar immigrants, became the first centres of activity and information for the postwar refugees. In isolation these groups lacked the unity which could help their fellow Estonians who awaited a chance to emigrate from Europe, and which could be used to make Estonian concerns heard in Ottawa. It was time to fill this gap.

Aleksander Weiler, a former member of the Estonian Parliament, initiated the idea of the Estonian Federation in Canada. The goals of the new organization were wide ranging, its activities varied and essential. The federation received great numbers of inquiries about immigration to Canada. Its directors' discussions with the Department of Immigration made possible the arrival of 100 Estonian miners and 95 of their dependents from Belgium.

Through the efforts of the federation, an international precedent was set in 1951 with the establishment of an Estonian Consulate in Toronto as the diplomatic representative of the Republic of Estonia which, though under foreign occupation, was internationally recognized as independent. For technical reasons Consul Johannes E. Markus initially had to refrain from political activity. It was not until October 1962 that the status of the diplomatic representatives of the three Baltic republics improved and the consul of Estonia was included in the list of representatives of foreign countries in Canada. From then on J. E. Markus appeared at all official diplomatic receptions in Toronto as the consul of the Republic of Estonia.

On April 29, 1951, the board of representatives of the federation decided to form the Estonian Central Council in Canada (ECC) as a subsidiary organization to coordinate efforts to educate the Canadian public and municipal, provincial and the federal government about the situation in Estonia. Over time, the ECC withdrew and became an independent organization.

The 10th anniversary of the Estonian Federation in Canada was celebrated with a.meeting and reception attended by Consul J. E. Markus and representatives of many organizations. Among the achievements of its first decade were the maintaining of contacts with the federal government, fostering cooperation with Baltic and other Estonian organizations, the production of radio broadcasts to mark Estonian Independence Day, a successful campaign to reduce the waiting period before receipt of the old age pension, the holding of assemblies to mark the anniversaries of Estonian statesmen, and support for cultural activities carried out by the local societies. The federation also sent a brief to the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, in which it stressed the need for first-language education for all ethnic groups in Canada. The Canadian Estonian History Commission was established at an executive meeting of the federation on May5, 1964.

In the internal political uproar brought about by the visit of the author Rudolf Sirge from Soviet-occupied Estonia, the federation adopted the following position: "The executive of the federation and its representatives on the ECC are resolutely opposed to the contacts and meetings with the Communist writer R. Sirge which have been organized during his stay in Toronto by certain of our public figures and writers." After Sirge's visit, it seemed that the Estonian community had lost its harmony and cohesiveness. At an executive meeting on February 2,1965, H. Kullango proposed that a congress of Estonian organizations be convened to formulate new goals for the future. The executive elected by the board of representatives on January 23, 1966, decided to devote all of the federation's resources to cultural matters.

The federation continued primarily as a representative body of Estonian societies and associations from coast to coast. Separate sections or committees of the federation have developed into new independent organizations, such as the Estonian Relief Committee in Canada, the Canadian Estonian History Commission and the Estonian Central Council in Canada. The federation has also fulfilled its function in uniting Estonian cultural and social organizations, encouraging the formation of local associations in places where none exist, providing ideas and leadership for their activities, supplying speakers for ceremonial occasions, supplying materials for local cultural activities, fostering ethnic consciousness among the young, organizing joint events, cultural conferences and art exhibitions. The major achievement of 1967 was Estonian Day at Expo 67.

The Estonian Central Council in Canada

As mentioned earlier, the central Estonian organization representing the interests of Canadians of Estonian heritage was founded at a meeting of the Estonian Federation in Canada board of representatives in 1951. The federation executive proposed the necessary amendments to the federation's constitution to form the ECC in Canada. The results of the secret ballot were announced on November 10, 1951, with 22 in favor of and six opposed to the amendment. A nine-member elections committee was formed with Juhan Müller, former minister of justice of the Republic of Estonia, as chairman. The number of elected representatives to the ECC was fixed at 17. The first elections among Estonians across Canada took place in 1952 with 80 candidates. There were 33 members of the first council - 12 elected members, 12 representatives from the federation and nine ex officio members. Johan Holberg was chosen chairman. The first years of the ECC were devoted to organizational efforts in Canada and the founding of an international union of Estonian organizations, based in New York, composed of representatives from the central organizations in various countries.